|

-0 |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

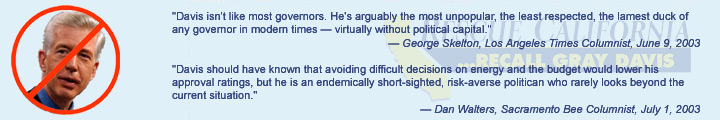

Only recalled governor faced plight similar to Davis' So they launched an ambitious drive to recall the governor. This, of course, sounds much like the effort to recall Gov. Gray Davis. Except it isn't. It was the recall effort against North Dakota Gov. Lynn Frazier in 1921. Frazier, whose socialist leanings and fiscal missteps were his undoing, was the only governor in U.S. history to be kicked out of office by recall election. His story bears remarkable similarities to the drive to oust Davis from Sacramento. "You need a combination of substantive disaster and personal distaste" to ignite a successful recall drive, said Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia's Center for Politics, and author of a book on governors. "You need a truly awful crisis – economic crisis, corruption – and the governor really does have to be disliked personally." Davis has become the most unpopular California governor in modern history. Those hoping to force the recall – recently ignited with the financial help of GOP Rep. Darrell Issa of Vista – say they have collected most of the 897,158 signatures of registered California voters needed to force a special election. Since 1911, when California voters adopted the recall process as a check on the power of their politicians, no petition to recall a statewide officer has made the ballot. Four state lawmakers have been recalled, as have several local officials. Frazier – first elected to the governor's office in 1916 – was a leader of North Dakota's Nonpartisan League, a party founded by former socialists who believed that a state-owned bank and state-run mill would protect farmers from private companies that were paying bottom dollar for grain and then overcharging customers for flour. But in 1920, the year Frazier was re-elected to a third term, farm exports began dropping nationwide and the economy took a downturn, exposing huge weaknesses in North Dakota's budget and making it impossible for Frazier to fulfill campaign promises. Moreover, when the state-run mill lost money, Frazier's office tried to hide the losses in the state budget. "About 80 percent of North Dakotans lived on farms, and it was sort of the only game in town," said David Danbom, a history professor at North Dakota State University. "Anything impacting farms had an immediate ripple effect on everything else." Davis' tenure has been similarly clouded by a sluggish economy and a $38 billion deficit that Davis critics say he tried to hide last year to win re-election. "(The 1921 recall) was similar in some ways to the situation that Davis is in – where he probably wouldn't be (facing a potential recall) if the economy hadn't taken a downturn," Danbom said. Davis also has been accused of mishandling California's energy crisis and ofhiring advisers with close connections or financial ties to the energy industry. Frazier's party put campaign funds in banks that eventually failed, and he created an agency that lent first-time home buyers no more than $2,500, although he allowed a party colleague to borrow $8,000. Much like today, it was conservative Republicans who launched the recall drive against Frazier. They had to get signatures equal to 30 percent of the number who voted in North Dakota's 1920 gubernatorial election. In California, Davis opponents need to collect the signatures of 12 percent of those who voted for governor in November. Frazier's foes got their signatures, and the recall election was scheduled for Oct. 28, 1921. Frazier was forced to run against Republican-backed candidate Ragnvold Nestos.

Dependent mostly on newspapers, pamphlets and public appearances, the candidates spent nowhere near the $25 million to $30 million expected to be spent in a

|

|

|