|

-0 |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

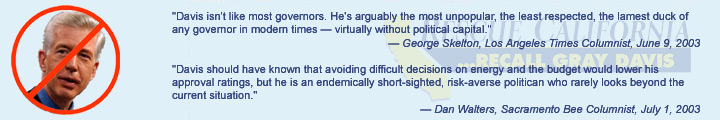

County at epicenter of recall rumblings The Coronado homemaker spotted the Gov. Gray Davis recall table on her way into Home Depot, made a detour, grabbed a pen and signed eagerly. "It just seems he has his hand in the till all the time and I'd like to slam his fingers in it," she said. Youseff Ghosn, however, wanted no part of it. "I never voted for him. I don't like the guy. But I don't like the system the way they're using it," said Ghosn, who owns a dental lab in Point Loma. "This is democracy. You vote someone in, you let it run its course." The petition drive to force an unprecedented gubernatorial recall election has brought California to the brink of a political earthquake, with San Diego County as its epicenter. An estimated one-fifth of the 800,000 signatures organizers say they have collected have come from San Diego County. In addition, the bulk of the money fueling the drive has come from Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Vista, who has spent $800,000 so far. "We have a very knowledgeable political activist base here," said former Assemblyman Howard Kaloogian, a Carlsbad Republican and one of the recall sponsors. "We've tapped into a popular sentiment that we thought was out there, but didn't know when we began." In addition, talk-radio hosts, especially San Diego's Roger Hedgecock and Rick Roberts, have relentlessly been beating the drum for the recall. "I'd change my position on human cloning if we could start with Roger," Kaloogian said. The drive to remove the Democratic governor is a unique exercise in street-level democracy. Clipboard-toting signature gatherers have been stationed outside supermarkets and retail stores all over the county. Some of the circulators are local political party activists. Some are devotees of conservative talk radio. Others are paid by the signature, by one camp or the other. Some are soliciting signatures for the Davis recall petitions, some for an anti-recall petition sponsored by Davis supporters, and some for both. "For a state like California that is so TV and radio-oriented, all of a sudden you have this going on, which is the ultimate one-on-one retail politics," said Steve Smith, who is on leave from the Davis administration to direct the anti-recall campaign. "It's very different for this state." Recall sponsors must collect the signatures of 897,158 registered California voters by Sept. 2 to force a special election, but they are hoping to get 1.2 million in case there are invalid signatures. They are aiming to turn in the petitions by early next month to force a fall election rather than combining a special election with the Democratic presidential primary next March, which presumably would give Davis an advantage. If there is a special election, voters would decide two questions on the same ballot: whether to recall Davis and who should replace him, if a majority supports the recall. A pro-Davis committee called Taxpayers Against the Recall, financed primarily by organized labor, is seeking to impede the recall by circulating a rival petition that condemns the campaign as a waste of taxpayers' money and an abuse of the electoral process. The anti-recall petition has no legal significance. But by paying $1 per signature, the Davis camp hopes to tie up as many professional petition-circulators as possible and drive up the cost of the recall. On Monday, the recall campaign raised its bounty from 75 cents to $1 per signature. Davis supporters often station their petitioners at locations used by recall signature gatherers.

"They are trying to get 1.2 million people to sign a petition and we are trying to convince those 1.2 million people that they don't want to sign the petitions," Smith said. "We're trying to put

|

|

|